As I was looking through my Twitter feed, I came across an article written by Amy Johnson Crow about lineage society applications that caught my eye. You can find her article HERE titled, “5 Things to Do When Applying to a Lineage Society.”

It got me thinking what I might be able to add from my point of view as the genealogist for The Society of Indiana Pioneers to compliment the great article that Amy Johnson Crow presented.

First Three Generations

Through the past nine years, I have seen a wide range of applications that have come in to our office in all shapes and sizes. Some are the just a few pages and others are literally 3 inches thick. From my point of view, I approach them all the same. The first three generations are always very straightforward: birth, death, and marriage information that come from official documents. These documents are the best way to confirm dates, places and give ties between generations.

Play Detective

One thing I notice is that a lot of people take the official documents as the absolute truth; I’m suggesting that you need to look a little closer. As we work with these documents, keep in mind what information is first-person in each document; birth records are first-person for the mother and the child’s information.

For death certificates, the only first-person items are the death date and place of death of the deceased and that is confirmed by the physician. All the other information is being given by grief-stricken loved-ones or even possibly by an institution’s staff. If you have ever been present during this point, you will understand that no one in the family is truly thinking at their clearest due to the stress of losing a loved one.

I have seen wrong middle names, wrong spellings of the deceased names, wrong birth dates, and wrong parent’s information. I always like to think of these items as being a confirmation of whatever I do find that is first-person as well as important clues.

The Human factor

The other part that plays into all this is the person that recorded the information – either at the time of the event or later as it is actually inputted into a modern document. For example, when I request a death certificate here in Indiana, either in the county or state office, they are referring to a book that has the information handwritten or typed which they then type or handwrite into a modern form for us to keep as our record. Do you see how many places that an error might creep in? What you need to know is that all the information is initially recorded in a row-by-row format, so each person’s information is all contained within one line in the recorder’s book.

It’s all in the recording

Are you thinking what I’m thinking? Oh, it has happened… I have seen where a very well-intentioned clerk literally started pulling information from the deceased person’s line of information and quite by accident, finished with someone else’s information. This error can be very evident if you are familiar with the person, but it can be very confusing when you don’t know that much about this particular person and suddenly you are now working with someone else’s information. (Talk about heading down the wrong trail!)

And the point to all this? Let’s just say that it is a good thing to look at all your pieces of documentation for a certain event and where one document doesn’t line up, then you might want to ask some questions of the preparing agency. At the very least, I would suggest you make a note of it for the society’s genealogist and acknowledge the item that doesn’t agree with the rest.

Power in numbers

When we get past those first 3 to 4 generations, things start to get trickier and that is where I start to look for multiple confirmations of a particular piece of information. For example, let’s look at birth records; most states won’t have official birth records prior to the late 1880’s, if that far back, so then we start to look at obituaries, tombstones, bible records, and yes, even biographies. When these things are added to census records, DNA results, and other documents that might not be official, you can put together enough circumstantial evidence for a good case within a particular generation.

Where a piece of documentation might not stand up well by itself, there is power in numbers. It helps me when an applicant pulls together all the clues and lists them together in a cover letter for that particular generation. It is kind of a cheat sheet for me to know where the applicant is wanting me to look for the information.

Crystal Clear

Check with the society’s rules, and if it is all right, then underline each important name, date and place so that the genealogist can easily see the item that you want them to see. This helps to make sure that the person reviewing your application sees everything you want them to see. I have had faint copies submitted, which I can handle, but if I am supposed to be able to find the pertinent information, it benefits both of us to have to information clearly underlined.

Here’s another hint: if you have a hand-written document, you might want to try and transcribe it and insert it along with a copy of the original document. Again, it is all about making it very easy for the genealogist to review your application and be able to see and read exactly what you want them to see and read! I’m very proficient at reading old script hand-writing, but it certainly helps to have something easy to read (to compare.)

Sleuthing

Here’s a tip that has helped me in the past: print out the application and work through your documentation like you are looking at it as the genealogist. As you work through each generation, you can then check off the dates and places of the each required piece of information. This process makes it painfully clear when you have a spot that is not documented as clearly as you might like.

If you have any weak generations(as far as documentation) this is where you then might consider making up a list of items that you believe make a case for a particular generation. It is hard to do when you are so closely involved in the actual work of obtaining all the necessary documentation, but trying to take an objective look at it is important.

It’s in the details

Be skeptical as you go through your work and make sure that you have every last bit of evidence covered in your presentation. (Of course, as I say all of this, each lineage society’s genealogist or registrar has their own vision of what the requirements are for the society. Personally, I try to make sure that I turn over all possibilities in order to help the applicant, but with other larger societies, they don’t have the luxury of time to track down any further documentation so it is truly dependent on the applicant to have all the available documentation on hand.)

Breathe

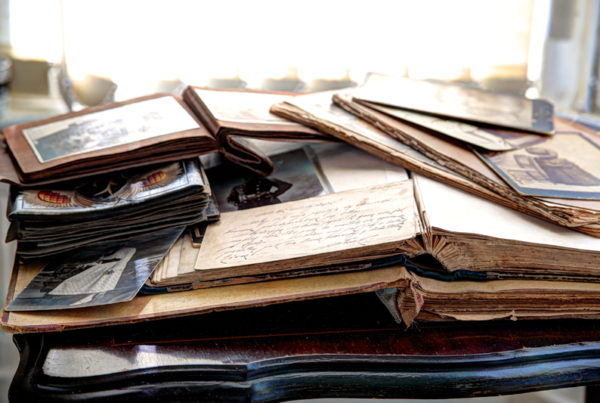

My best advice? Enjoy the process. Relish each generation. Once you are done with the application and have all your documentation, remember to go back and add stories and pictures to bring your research to life. It’s a Lifestory – your lifestory!