Who doesn’t love the thought of taking a peak into the lives of our families “way back when” in order to catch a glimpse of what their home life might have looked like? Let’s see… How old was my father and where did he work? What kind of house did they own and exactly where was it located? Why did they move around a lot or did they stay in the same home for years and years? These tantalizing questions are one of the reasons that we tend to spend a lot of time – especially in the beginning as we look back into our own family histories, gazing at the census records from so long ago.

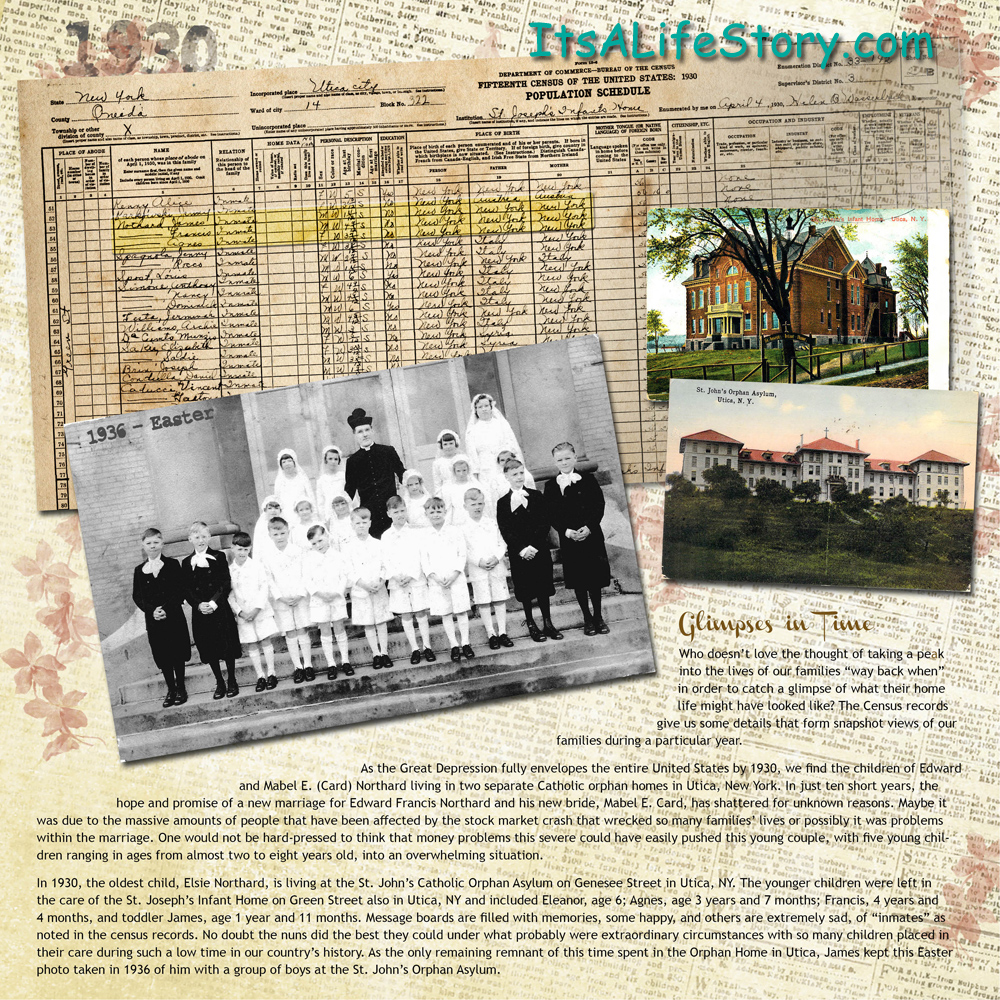

This layout is a single page from a LifeStory book where I combined a page from the 1930 Federal Census, photos, memorabilia, as well as related stories, facts gleaned from the census, and a bit of recorded history. (Census: Ancestry.com)

Many times we don’t have family story hand-me-downs(that’s me!) and the census takes on that look of a time machine so that we can become voyeurs of a sort. The one-line rows of boxes with information are carefully filled in with all sorts of great details gleaned from our own ancestors. Or were they? Can we rely on the census and take it literally as a source of information?

Details

I love census records. I love to see my family members’ names all written in tidy little sections – especially as small children. I love to picture them working on the farm and taking care of the daily chores. My father was just three when the 1930 census was taken in Pleasant Lake, Indiana right at the beginning of the Great Depression. What was life like for my grandfather as he tried to stay afloat and keep his family fed during this time of great hardships that spread over the entire United States?

Luckily, I was inspired a while back to talk with my own father several times to get some personal details but even now, I find that I didn’t ask enough questions and of course, I find myself heading back to the census records. My father passed away too early for me and then my mother, ten years before him, so I am now left with no contact with that entire generation. I understand the life cycle but it doesn’t make it any easier when I really yearn to understand more about them, their parents and their grandparents.

First Things First

I have done hundreds of searches over the years for my own family, my husband’s family, for clients and applicants of The Society of Indiana Pioneers as the genealogist for that group. I always find myself looking first at census records, after all, they go back 225 years to 1790. What becomes quickly apparent once you get familiar with the census records, is that the early ones, up until 1840, only give us the most basic information: head of household and number of family members within different age brackets.

That can be frustrating when following a family through those early years as we find some numbers that fit and others that do not fit in any way, shape or form. How can we tell who might be living in the household if we don’t have any names and worse yet, relationships listed? How are we supposed to fill in the blanks in our family histories when all we have are rows with numbers listed in them? Very carefully, I would answer.

This is the point that you truly put on a detective’s cap and grab for a spy glass and pipe. You have to become familiar with the whole family, not just the small nuclear family that we assume are the father, mother, sons, and daughters. We have to keep track of parents, grandparents, brothers and sisters who might also have their own sons and daughters. These are the faces behind those small little numbered columns of information.

History and Census Takers

Not only do we have to juggle all the family information but it helps to keep a sense of humor as we dive into these census records. After all, if you look back at the census-takers and the conditions that they worked in, it is little wonder that we still have the detailed records available today! After President Washington signed the first census act in March, 1790, it was up to the U.S. marshalls to locate and instruct census-takers and also to divide the country into suitable districts. The Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson sent out the marching orders to the marshalls, but the “devil is in the details,” wouldn’t you say? The enumerators of those early years didn’t have the luxury of a full-blown mail service and as a result, most information was taken one step at a time – literally.

Walking door-to-door or farm-to-farm takes on a whole new light when you put yourself in their shoes. Were there county line markers notifying the census-taker where to start and stop? What happened when a census taker would travel a great distance only to find that the folks living at the remote farm were not at home at all? Would he go back another day? Would he ask a neighbor? Or would he simply make something up or leave them off entirely?

Factual…

Even if the hardy sole took his position very seriously and made a point to get accurate information, how could he possibly know if the information he was given was factual? I wonder how many times an enumerator came upon a farmer in the midst of plowing or some other type of work and asked for detailed information about his children. That produces a comical picture in my mind because my husband has a hard enough time keeping all our children’s birthdates straight let alone knowing exactly how old they are. Add to that the fact that the father might have been working and you have the scene for some best-guess estimates, don’t we?

Or what about the wife who might not have liked the idea that age was creeping up on her and shaved off a couple of years? Even for myself, I have a hard time remembering exactly what age I am since I hit the 50 marker. For so many years, I joked that I was 40 and was more apt to actually keep that number in my head instead of my actual age. So, it is no wonder that we find census records with ages that don’t fit the 10-year add-on that we assume to find with each progressive census.

As you look at the census records, it is a good idea to keep in mind that those hardy souls writing down the information were only taking down what was given to them – no proof necessary. They also were not paid extravagantly either. In fact, it sounds like most of the earlier census-takers barely made enough to cover their costs while fulfilling their missions. Add to that the fact that they also had to make copies of their records before handing them in and it is again a wonder that we have the records at all! Up until the 1830 census, the enumerators had to write down their information on their own paper and then make copies on top of that. These papers had to be posted in a local place so that everyone in the area might take a look and make corrections. So much for that happening! And, so much for any privacy!

Foreign Languages in the Mix

With all the above obstacles, I haven’t even touched on the problem of language barriers that the census-takers faced. They didn’t have the luxury of having the form and questions translated into several languages. It is no wonder that names are almost unrecognizable and can be completely looked over unless you have an ever-familiar surname such as Smith or Jones.

How many people have searched census records for years looking for their missing family only to find that the name was written with no similarities to the original spelling? And what if the person giving the information could not speak English? How about trying to decipher a surname given in a foreign language? Oh, my, that could seriously throw a monkey wrench in the whole process and I couldn’t even blame the poor soul that was trying to simply do his job. After all, he was only supposed to write the information given to him. It’s at these times that we have to think phonetically and take into account the possibility of different accents. It’s a puzzle and you have to think creatively.

Plotting Changes

You ask what good is the census record if it is full of inaccuracies and could possibly be full of false information? Well, I would suggest that you keep that sense of patience as you carefully plot each family out using the available census records. Following a family from the start to the end can give you a great sense of the family unit as a whole and the pieces that you are missing. There is something very satisfying about plotting a family from its beginning as a newly-married couple through to their elderly years.

I track the family with names and dates as well as the ever-familiar “F” or “M.” Why add that last bit of information? Well, you will understand better the first time you realize that the census taker misunderstood a name and then thought it was a boy when it was a girl. That throws things off, but only if you are only looking at a census, one at a time. Literally, I will start a blank sheet and start to make those T’s like I would when I learned about debits and credits in accounting classes. The top of the “T” is the Head of the household and the family members are listed below on the right-hand side. I use the left-hand side to make notes, such as changes in towns or interesting tidbits that I might need.

Want to really take a deep look at the details that are right there in front of you? None of us enjoy rewriting tedious information, but you might find a blank census form that fits with the year you are looking at and copy your family’s information onto the form. Sometimes it is that simple act of writing down the information that brings new light to piece of information you might have glanced at a hundred times but didn’t catch until you had to write it down yourself. Yes, the old English class writing strategies do indeed come in handy when evaluating information and especially with our beloved census records!

So, go ahead and attach lots of census records to all your family trees, but if you really want to learn a bit more about your family, take some time, pick at the information one column at a time, and look at the information in different ways. You might find that all-important gem in amongst all the information hand-written by a diligent or somewhat diligent census-taker from years ago.